|

|

Soho bestowed E.B. White's gift of loneliness

on me during the summer of 1980, and I am still grateful.

From March through the end of August of that year, I

lived on Crosby Street in New York City's Soho, one

of the least transformed streets in this strange artistic-industrial

area. I was getting over a broken relationship, a five

year co-habitation that was, essentially, a marriage.

Soho is where I went to sort out my heart and mind and

to experience the many small and large devastations

that come with a broken love affair.

Soho bestowed E.B. White's gift of loneliness

on me during the summer of 1980, and I am still grateful.

From March through the end of August of that year, I

lived on Crosby Street in New York City's Soho, one

of the least transformed streets in this strange artistic-industrial

area. I was getting over a broken relationship, a five

year co-habitation that was, essentially, a marriage.

Soho is where I went to sort out my heart and mind and

to experience the many small and large devastations

that come with a broken love affair.

Soho

had great charm then, and, despite the colossal changes

that have taken place there, it does still. I found

that many of its unique characteristics served me well

in my period of convalescence. The first of these was,

simply, that not many people lived there twenty years

ago. When the long lines of trucks left the sides of

the streets in the afternoon, and the art speculators

and tourists fled with them, not many personalities

were left. For such a large area--even speaking of so

many years ago, I am excluding weekends--it was sparsely

populated. So that often I could be quite alone with

my loneliness, free to roam from street to street in

near or even complete solitude, feeling my melancholy

nurtured by silence and space. Hearing my own footsteps

clack and clomp in loud singularity during an evening

stroll was often antidote enough for some feeling of

wrack that suddenly overtook me. And it helped, at times,

to feel my hurt was the only hurt around, and Soho let

me feel that easily.

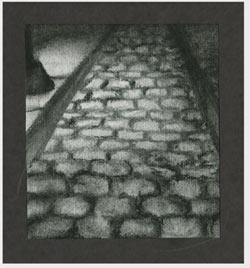

In

particular, this was true of my street, Crosby Street,

with its empty longitudinal expanse and its rough cobblestones.

At times, there was literally no one walking or driving

down this street for close to an hour. I would stand

outside

my building and communicate with this emptiness. I could

sigh deeply, as the heartsick are wont to do, and Crosby

Street, with great beneficence, ingested my woe, accepted

it, seemed to request more. It was constant in its willingness,

a big loyal mute friend that was always there when I

came home alone. I felt especially tender toward the

cobblestones. They seemed to me, even in their density,

a sort of delicate and vulnerable touch within the context

of all this cast iron strength. There were not a few

days when I spoke mentally to these cobblestones which

had so obviously been planted by human hands, and I

felt very protective toward them.

Soho's

sparseness also had the simple but startling effect

of granting a lot more attention to individuals. This

was an incomparable gift. It was not unusual, for example,

to see a single person walking on the opposite side

of the street, making it just you and him or her, strolling

for minutes along together on opposite sides, the only

humans around in all this real estate. I never saw people

more clearly, more distinctly than in Soho. That meant

much to me. It was a form of human contact that was

almost intimate--it was certainly private in one respect--and

if I didn't actually meet the person walking toward

me and then by me, I did feel there was an exchange

nevertheless. I can still remember faces and nods and

hellos and unabashed eye contact. This contact was my

first tentative reaching out for closeness again.

Because

there were so few people in Soho then, each person,

as I said, became dramatically unique in your eyes.

This was particularly wonderful with women. Soho had--has,

still, if you are observant--beautiful women, healthy,

energetic and alluring. There were times when I was

more grateful for that than for anything else. Women

I saw were often dramatically highlighted as they passed

by stark industrial facades and closed diners and empty

street corners. I could gaze at them for minutes instead

of seconds as is the case uptown, follow them and their

colors and clothes coming toward me, and even begin

a smile

almost a block away. It's hard to imagine that occurring

in Soho today. And they were generous with their smiles!

I can remember a pair of eyes, the way a dress clung

to a stomach, lovely legs, the way a woman turned a

corner and was off. I had four months of this display,

and though at times it made me ache with wanting, it

also made me feel vibrant and cheery and full of awe.

Those were feelings I sorely needed after leaving a

relationship that had left me numb and cold.

Another

of Soho's particularities that helped me gently through

the spring was its weather. Because Soho is a separate

commonwealth of sorts--I think its architecture has

a great deal to do with this--it seems to have its own

weather. This is singularly true of rain. A rainstorm

in Soho can have as much significance and drama as it

does on an island. During that particular spring there

were three or four very violent rainstorms, and experiencing

them in Soho was restorative. A rain in Soho always

brought out a childlike feeling in me. As the water

came washing down with pulsing force, I sat in my small

loft, huddled with my yellow lamps in the cool humid

obscurity, enjoying every noisy minute of it. I would

leave the windows open and thrill to the loud rain and

occasional spritzing I got as the wind blew some of

the storm into my room. The thunder crashed and rumbled,

and I felt an exquisite blanket of innocence and youth

and openheartedness as it rained and rained and rained.

There

were other attractions. Like playing basketball at Spring

and Thompson on the small court where local Italian-American

kids took up sides. They still do. Or the adjacent playground

where I used to come after work and watch children play.

And the gigantic R & K Bakery on Prince near West

Broadway, defunct now, which was one of the biggest--if

not the biggest in the city. "One day you're the

biggest, the next day someone else is," a worker

once told me. By necessity, it was a nocturnal operation.

I remember going out walking at 2 am and coming upon

four or five men in wrinkled whites sitting on a stoop

taking a breather as the building heaved out its concentrated

essences of fresh bread. That sugared wind snapped my

olfactory senses wide awake.

There

were a few special shops and stands, a favorite bar

or two, perhaps, and book stores. Bu though I liked

these very much, every neighborhood can usually claim

the same. It was in the end this superb gift of loneliness,

couched in so restful, poetic and accepting a manner,

that made living in Soho then so good, and made it so

difficult to leave. Soho had been with me in my time

of need. For four brief months I shared with it everything

I had, and it said, yes, all right, that's good. This

kindness had its effect. Because when I finally did

leave, I felt patched together not in some haphazard

fashion, but that the job had been done well, smooth,

strong and seamless.

email

us with your comments.

|

|

|