|

Chapter

1: At the Beginning

At

the beginning, there's a numb, nickel-sized buzz

just below my left ankle. I pretend it isn't there.

"Don't

cry, Annie-banannie," I soothe my little

girl; "if you don't want a broken cookie,

take a whole one." Tears rim her eyes, bright

blue, with black starpoint lashes. I nestle her

close and wipe them away. "Don't

cry, Annie-banannie," I soothe my little

girl; "if you don't want a broken cookie,

take a whole one." Tears rim her eyes, bright

blue, with black starpoint lashes. I nestle her

close and wipe them away.

No

time for pain.

"It's

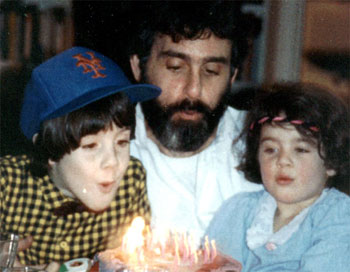

OK she touched it, Sasha," I josh her big

brother -- big, as in five. "We're family;

we eat each others' germs all the time."

I caress his warm cheek with my hand; cherish

the green-brown kaleidoscopes still opening in

his eyes, his lashes long as awnings, his size-four

feet that barely touch down.

*

Something

terrible is happening to me.

The

ob-gyn said the numbness would disappear once

Anna was born. But in two years it's spread across

the bottom of my foot and up the other ankle.

Why

is it spreading? What's wrong?

Forget

it. Don't think about it.

*

Something

is making my fingers tingle, and buzz, and go

numb.

"Sasha,

sweetheart, please stop squiggling so I can button

your shirt. We'll get to the swings much sooner

if you stay still."

Why

can't I feel buttons anymore? Find buttonholes?

Fish dimes from my wallet?

Maybe

I'm always in a hurry . . . .

*

Something's

jabbing my left foot -- like tiny medieval demons

wielding hot pins and needles, and plunging them

deep.

Could

there be nails in my shoe?

A

year ago, they were torturing my ankle.

"Ouch!"

Six

months ago, they started gouging my calf.

"What's wrong, Mommy?"

Now

they're attacking my thigh.

"Sasha,

is there a pin stuck in the back of my jeans?"

"Nuh-uh,

Mommy; nothing there."

What

the hell is going on?

*

"Bedtime

-- book time," I call.

One

bright-white polka-dot of light pulses in my left

eye . . .

"I

pick first," Sasha yells.

"No,

it's my turn," Anna yells back.

It

flashes like a shorted-out bulb . . .

"Let's

snuggle up and read both, you guys."

Like

a pin-dot blind spot.

"Once

upon a time . . . . "

Shut

up! No time for melodrama -- just read.

"When

wishing still counted . . . . "

*

Something

makes my skin so sensitive that the swish of my

summer skirt, the warm silken water of the lake

at Stockbridge, even the stroke of Jim's hand,

sears across my leg like acid.

"Um,

Sweetheart? The other leg now?"

Dear

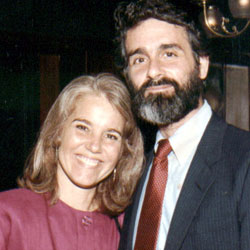

Jim -- my smart, sexy, high-watt husband. He's

so overwhelmed by his labor law practice; how

can I add one more worry? Nope; not one whisper

about these wacky symptoms.

*

What's

filling my leg with strange static? Why does it

scatter sharp sequins of pain with every step?

Am

I just imagining this? Am I a hypochondriac, wanting

attention like my mother? Not if I don't tell

anyone. Well, imagining something beats having

a real disease. Though that makes me crazy, right?

Wrong. And nobody could invent this pain. I'm

blessed with a florid fantasy life -- but, hey,

I write kids' TV, not horror flicks.

*

Now

the edges of my left leg shimmer and blur -- as

if Scotty started beaming me up to Starship Enterprise,

then forgot to finish the job.

Sasha

twirls in a giddy circle: "Six, six, I'm

almost six! Say about my birthday party again,

Mama."

"Well,

we'll go to the Central Park Carousel with all

your friends . . . "

How

will I ever walk all that way?

"And

we'll play Pin The Tail on the Wolf . . ."

And

back?

"

. . . and I'll bake you a big green birthday cake

-- "

"Green's

my favorite!"

Don't

think; just do it.

*

Something

in my body is moving between the brutal and the

bizarre.

"Push

my swing, Mama," calls Anna.

"Mine,

too," calls Sasha.

Something

makes me gray with fatigue, till the joy of pushing

my kids on the swings becomes a sheer act of will.

"Push

me higher, Mommy, higher! I want to fly,"

Sasha sings out.

Hot

spots light up and burn along my arms, neck, and

ears -- as if some sadist were rubbing them hard

with Szechwan peppers.

"Look

at me, Mama -- my toes touch the sky," Anna

sings back.

Stop

it! Don't dwell on it.

"Look

at me!"

Think

about something else.

"Look

at me!"

Think

about how beautiful your children are.

I

don't have time to be sick.Think

about Jim's sweet dark eyes.

I

don't want to be sick.

Something

terrible is happening. And it's getting worse.

I

won't let myself be sick.

I

can't make it stop.

I

won't let anything hurt us.

Something.

*

* * *

* *

After

two years of silently enduring these mysterious,

increasingly severe symptoms, I both want -- and

fear -- a diagnosis. I'm afraid of what this physical

cacophony means, yet need a name for the strange

and frightening sensations reverberating through

my body. When I finally tell my internist, he

packs me right off to a neurologist he describes

as brilliant, no-nonsense, and thorough.

Right

on all counts; except he forgets to mention that

Linda Lewis is also an attractive Amazon of a

woman -- over six feet, with prematurely white

hair cut short and blunt; big gray eyes behind

glasses that make them even bigger; thick black

lashes and brows in a strong face with wide cheekbones

and a generous mouth. Her large hands look capable

of doing anything well, from setting broken bones

to rappelling down a mountain. She listens carefully

to my strange conglomeration of maladies, asks

a few incisive questions, but mostly just listens

as I describe what I feel.

When

I finish, she makes a quick sketch in red ink

on one of those human-body coloring-book-type

outlines neurologists keep close at hand for recording

afflictions. Her sketch uncannily mirrors my own

mental picture of my pain -- which feels so tangible,

so "visible," that I envision it as

a network of chartreuse neon lines criss-crossing

my body. Now, there it is on paper: my own chartreuse

images -- transmogrified, but heard, understood,

recorded.

"You

probably thought you were crazy, but you're not,"

Dr. Lewis says. "These sensations may seem

peculiar and unrelated to you, but they draw a

very clear picture for me: they follow the nerve

roots all over your body."

So

it's real. I have objective confirmation. I take

a deep breath for the first time in months. She

understands me -- and my pain. I will be eternally

grateful just for that.

But

a split-second later, it slams into me: corroboration

is very cold comfort. Something is really wrong.

While

I struggle with this paradox, Dr. Lewis writes

a flurry of blood test and laboratory slips, then

hands them to me.

"These

tests are used to diagnose nerve disease. Maybe

they'll make the picture clearer," she says.

"Come back when I have the results, and we'll

see."

*

* *

I quickly learn to loathe the EMG, or electromyograph,

more than any other neurological test. First I

ride the elevator to a suspiciously quiet floor

at the Neurological Institute. I go alone on the

premise that this is my body, and I should begin

now not to inflict my clinical trials and tribulations

on anyone else. I shed my clothes and identity,

and don an especially limp and frumpy hospital

"gown." Then I wait an unconscionable

length of time in a frigid little cubicle until

a white-coated Ph.D. appears with no greeting

or apology for the long delay. With no explanation

whatever, he orders me to lie down on a narrow

examining table, grunts "Don't move,"

and -- with absolutely no preamble -- jabs long

pins attached to electrodes and wires deep into

the most painful parts of my most painful muscles

until they make contact with my most painful nerves.

In my efforts not to scream or kick, I force myself

to think about something -- anything -- else.

Dr. Josef Mengele comes immediately to mind.

"We

will now begin the procedure," he announces

to a spot somewhere near the overhead light fixture.

Begin?

I thought it was almost over.

"Don't

move," he repeats. I wouldn't dare.

With

this, Dr. Sadist turns on the electric current

that feeds the needles stuck in my legs, then

blandly and cold-bloodedly records my pain as

a wavy graph on what looks like a TV screen. It

now feels as if my legs are hard-wired into several

dozen electrical sockets. Or maybe the way it

feels when I crack my elbow on the edge of my

desk. I think it may feel like the neurological

equivalent of the electric chair. Unfortunately,

I do not die, though it crosses my mind as a rather

attractive alternative.

I

actively question myself as to whether I am merely

being a wuss about all this until I learn that

a certain well-known professional football player

tore the electrified pins from his legs and ran

cussing from the Procedure Room because he couldn't

bear the pain. In many ways, however, this is

irrelevant. He could still run; I'm too undone

by pain and indignation to think of lifting my

foot.

Finally,

just before I start to smoke, Dr. Mengele turns

off the machine. While I'm still limp and quivering,

he yanks out the needles and announces, "Time

for Evoked Potentials."

Uh-Oh.

He

calls a lowly technician into the room. She fries

the surfaces of my arms and legs with special

infra-red lamps. When I am broiled to the proper

sizzle, he attaches new, circular electrodes to

highly sensitive spots on the surfaces of one

arm and one leg in order that he might administer

a series of increasingly intense electric shocks

to my nerves and record exactly how long it takes

me to twitch. I try to remind myself that both

these modern medical variations on the medieval

rack are designed to yield objective measurements

of how quickly my nerves receive and relay information

to and from my muscles and spinal cord. But even

before the results are in, I know these tests

prove one thing unequivocally: I am a total coward

when it comes to pain -- any pain, but particularly

gratuitous pain. Of course, I could have told

them that before enduring any tests at all.

*

* *

Dr.

Lewis remains undaunted when she calls to tell

me the test results are equivocal -- they reveal

no clear pattern of nerve damage. She now announces,

in what I'm learning is her characteristically

cavalier fashion, that it is time for a nerve-and-muscle

biopsy. This turns out to be an utterly excruciating

little surgical procedure in a real-live operating

room. Using only local anesthesia, a lively, handsome

young neurologist named Dr. David Younger will

remove about a tablespoon of muscle and just a

smidgen of sural nerve from the back of my left

calf for examination under a microscope. Unfortunately,

I must be fully conscious during the entire operation

so he will "know" when he cuts the nerve.

Barely

two weeks later, I'm in an operating room, lying

prone on a narrow padded table that looks more

like my Nana's ironing board than I would have

imagined from Hollywood versions. In fact, nothing's

quite what I expected: the small, white-tiled

room looks a little like a kitchen; the nurse

has a beard and tells me how much his little girl

likes Reading Rainbow, the children's TV series

I write; and Dr. Younger not only has a soul but

a sense of humor.

It

takes far more digging to find that skinny skein

of nerve than either of us like, but we chat quietly

about religion, Brahms, this-and-that while he

pokes around in my left calf. The surgical nurse

holds my hand whenever he's not busy, and we all

make awful puns about having a lotta nerve, being

nervous, etc.

But

when Dr. Younger finally hits that nerve, there

is absolutely no doubt: he knows. So does everyone

else anywhere near that crowded, stuffy little

room. When he severs the nerve, pure pain explodes

in my leg, drills up my spine, and makes me puke.

Yet

even in hell there are funny moments. As soon

as I finish retching into a stainless steel kidney

basin, I croak, "How come when you cut a

nerve in my leg, I throw up?" Dr. Younger

doesn't miss a beat: "Don't you know the

leg bone's connected to the stomach bone?"

Then,

taking my question seriously, he stops cutting

and explains, "Local anesthesia blocks some

transmission of pain to your brain. But your body

always knows when it suffers an insult like this

-- and it rebels."

His

compassionate explanation makes me feel human

again -- not like some wide-awake corpse getting

dissected. He looks at me very kindly, and asks,

"Are you really OK? I hate to hurt you. We

could take a little break if you need it."

"No,

I'm OK," I say.

Then,

as if rehearsed, he and I and the nurse, who's

still holding my hand, launch into a rather off-key

rendition of "Dem bones, dem bones, dem dry

bones" as he finishes removing muscle and

starts sewing the first of 29 stitches. I know

I will love this guy forever.

*

*

*

It

takes almost two weeks to get the biopsy results.

My first hint that something must be wrong occurs

late on a Friday afternoon, when the internist

tips me off with a phone call. This in itself

is surprising on a brilliant October day at the

start of a peak leaf-watching weekend. What's

a doctor doing in his office at 5 PM on a Friday?

"You

speak to Linda yet?" he asks much too casually.

"About the biopsy? No, not yet," I answer.

Uh-oh, I think; something's wrong. I start churning

out disaster scenarios: Cancer. Degenerative disease.

Amputation. Death. Stop

it!

"Well,

she's been trying to reach you, so you'd better

give her a buzz," he says.

"What

does it show?" I ask. He suddenly becomes

very busy.

"Gotta

go," he says; "talk to Linda."

And he hangs up.

The

phone rings again. It's Gloria, "Linda's"

secretary.

"Miss

Schecter? Dr. Lewis would like to see you at her

office next Monday at one. Dr. Younger will be

there, too. Can you make that?"

"Uh,

yes," I stutter, "b-but could we come

right now? Or -- could I just talk to her about

the biopsy results?"

"No-no,

she's too busy; she can't come to the phone. But

she definitely wants to see you Monday."

"We'll

be there. But -- couldn't I just speak to her

for a minute?"

"No,

she's leaving right now for a weekend in the country."

And

that was that.

*

* *

Our weekend looks normal: wall-to-wall kids, terminal

exhaustion and, for me, what's now "normal"

pain plus breath-snatching post-op anguish. Jim

and I always take turns getting up early with

the kids on weekends -- instead of snuggling together

in bed and getting interrupted every two minutes,

one of us sacrifices so the other can catch up

on lost sleep. Saturday it's my turn, so I'm up

before dawn with the kids, who bounce around smelling

fragrant as fresh-baked bread still warm from

the oven. We cuddle inside a quilt on our window

seat overlooking 72 and West End, watching the

West Side wake up: first the garbage truck parade,

then a rising tide of buses and cars, then yawning

dogs walking their yawning owners.

Our

high point is always the dog across the street.

Each day at 6 am, the doorman at 253 West 72 ceremoniously

opens the door for a scruffy blond dog who pads

slowly to the corner Korean deli, fetches the

Times, then returns home holding the paper proudly

in his mouth.

Jim

and I always try to walk the parental high road:

no-sweet-cereal, no-violent-cartoons, only-one-hour-of

TV-a-day. But when exhaustion clamps down hard

-- like today -- I crash on the couch and settle

for second best: replay #4,358 of The Land Before

Time, Sesame Street, or another "worthwhile"

video. Instead of sugared cereal, I serve pretzels,

milk, and Granny Smith apple slices. After my

nap and a real breakfast, we all get dressed.

Then, hobbling on a cane and flattering Sasha

into pushing Annie's stroller, I take the kids

to the Museum of Natural History while Jim goes

to the office to prep for a trial. I sink to the

floor in the Dinosaur Hall and nearly weep when

a guard hustles me back onto my numb and painful

legs. Sunday, we three head for the playground

in Riverside Park with a picnic while Jim goes

back to work -- Jim's trials are always my tribulations.

Beneath

the mundane -- between pb&j sandwiches, endless

cups of apple juice, macaroni and cheese, spaghetti

and turkey balls, and bubble baths with my hands

shooting so many electric sparks I almost expect

to electrocute one of us -- I have a sense of

the beach sliding out beneath me in an ebbing

tide.I feel like I'm walking on top of a thin

m&m sugarshell reality that I will crash through

on Monday at one o'clock.

What's waiting there, underneath?

*

*

*

Monday brings full-blast sunshine, an intense

autumn-blue sky, and trees fairly shouting with

color. But it's never a sunny day inside the Neurological

Institute, no matter how vibrant the weather is

right outside the sliding glass doors. The light

is always a waxy, hideous yellow fluorescent that

makes the healthy resemble the dead, and the unhealthy

gray as mummies and even more horrifying. The

floor, waxed too many times, is too slippery for

canes and crutches, and there are never enough

seats for the infirm to perch on while we wait

in utter silence for the maddeningly slow elevators.

I try not to see the people with Frankenstein

stitches showing through the new stubble on their

scalps; others with completely empty eyes slumped

in wheelchairs; and the walking wounded who limp,

shake, drool, and drag their feet. A few poor

souls get walked along like flaccid, obedient

dolls, or dogs on invisible leashes, by hollow-eyed

relatives or unconcerned aides. Some simply stare

at the ugly linoleum and cry. Two, three, five

minutes in that lobby and I feel waxed to the

floor -- helpless, hopeless, inert.

All

this, just waiting for the elevator.

"Elevator

going up," chants a mindless recorded voice.

"Elevator going up, watch the closing doors."

Thank you. Just in case I never thought of it

before, the voice reminds me that nerves feed

my eyes as well as my muscles.

The

action picks up as soon as we reach the second-floor

waiting room. This is it, the moment I've been

seeking and dreading: my post-op, diagnostic consultation.

Drum

roll, please.

But

now something weird begins to happen. I quickly

discover the great advantages of denial -- a psychological

state which allows persistent negation of the

undeniable facts right in front of your nose --

an evasion I'd always assumed was "bad"

and "weak" and thus reserved for weenies.

But I am about to discover that denial is actually

good. Very good.

Jim

and I sit in the over-crowded waiting room, alternating

between stiff silence and irrelevant giggling

over nothing. His hand holding mine is icy. Slippery.

I try to concentrate on the new and attractive

decor.

An

agitated woman rushes into the room.

"Are

you Ellen Schecter?" she practically yells.

I nod, and she hands me an envelope with my name

typed on it. Misspelled.

"Dr.

Lewis said be sure to read this before she meets

with you."

She exits quickly, as if relieved to get away

from us. I never saw her before, and never see

her again.

Jim

and I move even closer together and read the letter,

clutching cold, sweaty (in my case numb) hands.

|

Dear Ms. Schecter,

|

|

As

you know, the biopsy is abnormal . . . .

It indicates demyelination with axonal changes

. . . . The teased muscle fibers are abnormal

. . . . demyelination in sensory, motor,

and autonomic nerves . . .

|

"What

does this mean?" Jim asks.

"Not

sure. But demyelination -- not good. That's the

protective coating on the nerves -- "

"Right."

We

read it again. And shrug, mystified. We don't

like that dreaded word "demyelination."

It could mean ALS (Amyotrophic Lateral Sclerosis,

AKA Lou Gehrig's disease) or Multiple Sclerosis,

or who knows what horrible "osis" we

know nothing about.

"Where

the hell is Dr. Lewis?" Jim asks.

We're

so nervous we get punchy. But before we have a

chance to do more than whisper and giggle nervously

like naughty high school kids about this hot tip

we can't decipher, Dr. Lewis appears -- she looks

especially stately today -- and asks us to come

into her office. She doesn't look happy. Or sad.

She tries to watch me walk without appearing to

watch me.

Neurologists

have a bad habit of doing this. They walk behind

you to check out your gait: do you limp? drag?

stumble? wobble? It must be a little trick they

learn in medical school: Remember to use every

available opportunity to observe the patient without

being observed. Rather sneaky, though I actually

prefer it to the alternative: The neurologist

commands "Walk!" and I must perform

a humiliating (in my case lopsided) promenade

up and down an examining room or corridor under

intense scrutiny while wearing a deliberately

frumpy shmatah -- gaping open in the back -- that

the medical community insists on euphemistically

dubbing a "gown."

I

try to walk behind Dr. Lewis so she can't watch

me limp. Because, in fact, it's hard to walk and

I must move slowly while using the cane. I still

can't put my heel down on the floor, and the merest

brush of my skirt against the two biopsy incisions

on my left calf is excruciating. Pulling on panty

hose is an exercise in determination versus agony

that leaves me in a cold sweat. I know she knows

my incisions hurt, but I also know she cannot

imagine how much. I'm afraid to tell her. It will

make it much too real.

She

keeps trying to sidle behind me, and I keep trying

to slip behind her. It's an awkward little minuet,

and once again I give a half-giggle.

"Nice

skirt," she observes. "New?"

I

nod yes.

"Trying

to hide the scars on your leg?"

This

is her version of small talk.

Kind

Dr. Younger still hasn't arrived by the time we

file into Dr. Lewis's office. I sink gratefully

into the maroon leather chair in front of her

massive mahogany desk, which is roughly the size

and heft of a coffin. I notice that the room has

been redecorated since she sent me for surgery.

Someone worked quite hard to re-create exactly

the same perfectly dull and innocuous 1930's "Consulting

Room" style it had before: same ugly no-color

cretonne drapes, same old tomes with depressing

titles -- Brain Tumors, Multiple Sclerosis, Diseases

of the Nervous System -- same leather chairs with

brass studs, same enormous desk piled with files,

same little examining room off to one side with

white enamel cabinets, basins, and sharp-pointed

instruments displayed behind glass doors. This

all-white chamber of horrors is already haunting

my sweatiest nightmares.

I

sit there inhaling the musty air, and imagine

John Gunther sitting in this chair in this room

with the same Thirties' smell, maybe even the

same dust motes dancing in the sunlight, making

mental notes for his book, Death Be Not Proud.

I imagine his heart breaking as he tried to escape

into the ugly pattern of meaningless arabesques

on this same rug while a doctor informed him that

his beloved young son will die from a brain tumor.

The

place still reeks of stale sunshine and despair.

I wonder how many other people before me sat in

this same massive leather chair -- much grander,

probably, than the ones they have at home -- waiting

for the watershed news that slices lives forever

into Before and After.

I

imagine them, like me, trying to calm down and

stop shaking, trying to conjure up all the rational

questions I can't remember or haven't thought

of yet. Like all those other poor suckers, I take

deep, reassuring breaths as I convince myself

that the news cannot be all that bad. Denial.

I glance at Jim: his sweet dark eyes look even

bigger than usual; frightened and a little too

shiny. He still grips my hand, white-knuckled,

as if he's afraid I'll float away from him.

Dr.

Lewis wears a blouse that at first glance resembles

silk but is really polyester. 'Less up-keep,'

my desultory brain muses. This blouse is crimson,

which looks especially handsome with her prematurely

white hair and big gray eyes that look pretty

even without make-up.

I'd

love to see her wearing mascara just once, I think,

drifting further into the Denial Zone. The make-up

tangent, designed to keep me thinking about anything

except what's happening to me right now, reminds

me of a story I heard from another patient. She

told me how Dr. Lewis suddenly appeared in the

hospital one New Year's Eve just before midnight

to check on a dangerously ill patient; how everybody

stopped breathing for a moment when all six feet

of her swept into the ward in a floor-length swathe

of black velvet. I fall in love all over again

with that image of her: the avenging Doctor-Angel

guarding her patient from Father Time's scythe,

robed in black velvet, glittering with the sharp

scintillation of knowledge and know-how and diamonds

. . . except, wouldn't she wear rhinestones? She's

far too practical to spend all that money on diamonds

. . . .

The

image dissolves and I concentrate on the sun motes

dancing haphazardly in front of the window. It

probably hasn't been washed more than two or three

times in the decades since John Gunther's son

died.

Throughout

my reverie, Dr. Lewis rustles papers into piles,

sorts pens and pencils, puts large paper clips

around the letters and lab reports bulging out

of my rapidly expanding chart. I watch the clips

immediately slide off again. She avoids looking

at me. She chatters about something very neutral

and irrelevant, so I go back to the sun mote ballet,

humming the Sixth Brandenburg Concerto in my head,

and waiting for the movie to begin.

Now

she clears her throat, pushes her glasses back

up her nose, shoots one quick look at my face,

then tries fitting a large, evil-looking pincer

clip around the unruly papers. It bites and holds.

She clears her throat again, looks up, and says,

"Well,

you've got a disease."

email

us with your comments.

|